What to America is John Brown?

On December 2, 1859, the United States carried out its first execution of a prisoner convicted of treason: a white man who challenged slavery. Today, America still can’t imagine a nation of white people who dissent from white supremacy. That’s partly because we can’t imagine healthy dissent.

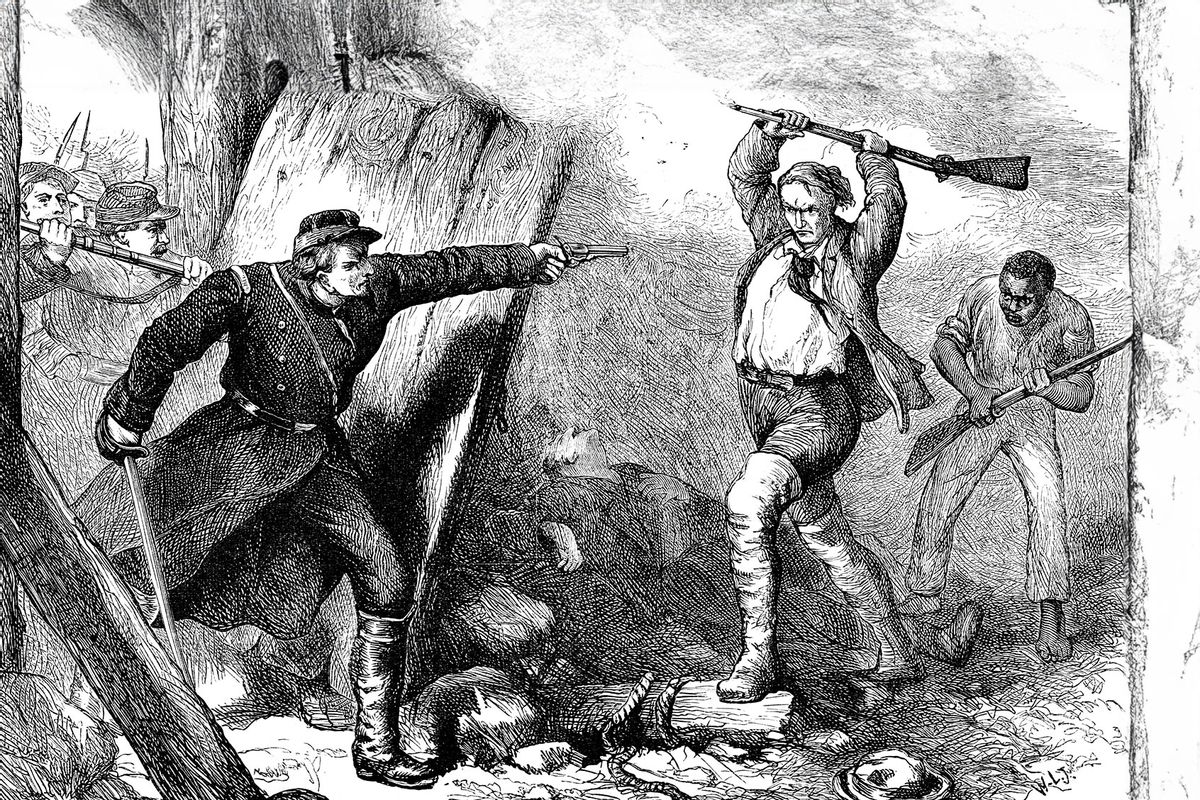

As a professor of peace and conflict, I am often teased about my support for the 19th-century militant John Brown. Peace Studies involves studying alternatives to violence, and certainly not the advocacy of violence, so I admit that Brown is a difficult figure to square with my work facilitating multi-partisan and multi-ethnic collaborations. Brown, who was hanged in 1859 for raiding a federal armory in Harpers Ferry, VA, aiming to support enslaved people’s escape to freedom, had also clashed with pro-slavery groups during the battles known as “Bleeding Kansas,” including an alleged midnight ambush and slaughter of five pro-slavery leaders.

After decades of giving speeches arguing against slavery, and leading conversations and appeals to the wealthy and powerful, Brown was impatient with this pacifist approach, which insisted on “moral suasion,” as mainstream abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison called it — what we’d now call “changing hearts and minds” or “changing the narrative.”

His dear friend Frederick Douglass, in a now-famous speech given two years before the Harpers Ferry raid, asked a white audience in Rochester, NY, “What, to the slave, is the Fourth of July?” answering that the day merely reminds of, “the gross injustice and cruelty to which [Black people are] the constant victim,” and exhorting

your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled.

Douglass and Brown were not the only ones impatient for their peaceful dissent to finally be heard. In those febrile years, Brown and many others took up arms; 18 months later the country plunged into a long, bloody civil war.

What, to America, is John Brown? Maybe a lesson about people who refuse to learn from the instructive dissent of social movements, whatever “side” they’re on. But the fact that there are only three statues of Brown in the country tells us something of a particular shame attached to his legacy. I don’t think the shame is for his violence. I think it’s for our white history of coordinated repression, instead of the moral courage needed to finally create a just, multi-ethnic democracy.

Dissent from white supremacy now is quite different than in Brown’s day. The war that to Brown had clear “sides” — white pro-slavery forces against Black enslaved people — has grown more dynamic and complex. Legal sanctions have closed a gap, bringing far more protections for Black and other marginalized people, so that uninformed white people can reasonably object to what they perceive as “special treatment” for other groups. And relying on people’s racial identities alone doesn’t deliver justice, since wider economic opportunities have unsurprisingly also resulted in abuses of power by people of all races, not just white people. Today’s scenarios thus require both information and discernment. Mamie Till-Mobley wrote in 1955, after her 14-year-old son, Emmet Till, was lynched in Mississippi:

People have to face themselves. They have to see their own responsibility in pushing for an end to this evil. Two months ago I had a nice apartment in Chicago. I had a good job. I had a son. When something happened to the Negroes in the South I said, “that’s their business, not mine.” Now I know how wrong I was.

Till-Mobley, a Black mother who lost her son to mob violence, and then because Jim Crow courts had no recourse to the state, urged all individuals to take responsibility, not only members of the racial group that killed her son. To me this isn’t a false equivalency, somehow erasing the very different obstacles that Black people faced and which white people put in place, but a generous gesture acknowledging that everyone in society is tied together, whether we want to admit it or not.

In February of last year, I flew to Kansas for research on John Brown and stopped in St. Louis to visit family. I was especially looking forward to talking with my cousin Will, who’s ten years younger and also a fan of Brown, describing him in our texts before my trip as “absolutely a man of noble character.” I wanted to trade facts and sources; also, because he did two Army tours — Iraq and Afghanistan — I expected he might have a different understanding of John Brown’s view of violence as sometimes necessary. I was hoping to learn something.

But the fact that there are only three statues of Brown in the country tells us something of a particular shame attached to his legacy. I don’t think the shame is for his violence.

Will’s sandy blond hair is receding a bit, and his eyes have an insomniac’s circles. Built like a distance runner, he thinks and talks fast, his stories peppered with Army-vivid swear words.

After describing settlers’ westward expansion (“Big fan of [President] Polk — that rope-a-dope in the Spanish-American war?!”), Will shares his assessment of most liberal policy approaches, starting with FDR (“influenced by the fascists”) and continuing with Black Lives Matter (“[morally] bankrupt”). With each of his points, I can feel the gap between us widening, at least politically. I resist automatically assuming I’m right, particularly about facts I haven’t yet researched. I note that he grew up white in St. Louis, raised within white settler culture; I grew up white in majority-Black Washington, D.C., going back and forth from the dinner tables of white families, of Black families, and Black immigrant families, each one offering me a very different interpretation of the day’s news.

Will is also a good listener. As I share how differently I see, for instance, Black Lives Matter and the Black freedom movement in general, he looks for areas where we might be saying very similar things but using different language. An area we’re not able to find a connection on is the police. And I flinch when, instead of saying someone’s tough, he uses a phrase like “they’d rip your heart out,” though I’m guessing it also reflects the Army culture.

Maybe it is my flinching that causes him to text me after I leave, one of his essay-long musings on life philosophy with politics that begin with, “hey man.” While talking I’d brought up the fact that the curator at the John Brown museum in Osawatomie, KS, had described Brown as an “ideological guerrilla,” and I couldn’t help but be reminded of the rioters at the Capitol on January 6. They too saw their acts as patriotism, not treason, a moral dysphoria that I see repeated in newspapers’ use of the word “extremist” to describe dissent that is escalating or confrontational, even angry protesting. Disruption is never neutral, so to me, the question is: To whom are disruptive acts accountable? Is it only the powers-that-be, or are the actions seeking to instruct on how those powers can act more justly?

I asked Will about his thoughts, and whether the Army had codes of ethics that might be relevant to understanding how far might be “too far,” and whether force is sometimes necessary. But he gently dismisses my line of questioning, saying that whatever ethical code he follows he’s arrived at from hard experience, and we are quiet for a minute. Later, asking why I have such a strong interest in race, he seems sensitive to the possibility that my learning, too, has come from hard experiences. Which is also to say, my mistakes.

In his long text a day or so after I’m home, he seems to have thought more about my question, and maybe also wants to make sure I don’t stereotype him as “conservative,” let alone an extreme conservative, conclusively describing Brown’s choice, “to engage in such a harsh and extreme f***ing manner” as not having “any place in the here and now of American politics.”

Will is open to my dissenting views, even when I vigorously push back, and I have grown in my understanding of his. We’re learning from each other. But too often views that dissent from white supremacy norms receive disdain and correction. In a university talk a few years ago, after I brought up Brown calling slavery a “war” that’s “one portion of its citizens against another,” a white woman scholar advised me to “look in the mirror a bit more about your own biases.” I felt rebuffed and judged, and questioned whether I’d come across as arrogant. She also hadn’t responded to the substance of what I’d said, which I was genuinely interested in hearing.

A key part of conflict resolution is knowing how to discern a “third way” and not only the “two sides” before you — also known as learning.

In “My Bondage, My Freedom,” Frederick Douglass noted that plantations were not just places, where enslavement was legal, but a political project, a “nation in the midst of a nation… [whose] branches reach far and wide in the Church and State.” And which, to maintain “fetters on the limbs of the blacks” proposes “to padlock the lips of the whites.” Douglass was referring to violence, whether by lynching and assault or by destroying people’s property, threatening their livelihood. (I’m grateful to Saidiya Hartman for bringing the Douglass piece to my attention in her 2020 interview in Artforum.)

In this century, the more common tools for repressing dissent are disinformation campaigns, which carefully depict the idea as disloyal or dangerous. “Marxist,” for instance, is still a chilling synonym for “anti-American” in many conservative circles. Like “McCarthyism,” Senator Joseph R. McCarthy’s 1950 crusade against Americans allegedly exploring communism, this kind of repression goes viral and can result in widespread retaliation, firings or censuring, as is happening now toward many who express pro-Palestine views. They are, instead, described as “pro-Hamas,” or worse, as violent terrorists. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote an article in response to McCarthy, “The Freedom to Learn,” noting that simply for exploring alternatives to the economic system one was likely to be called a traitor, “accused of having selfish and unfair designs upon the progress and well being of the people of this nation.” It’s not just the accusation of treason he reviled, but the active efforts to bar access to information, to learn:

not only what our leaders say, but what the leaders of other groups and nations, and the leaders of other centuries have said….[access to] such an array of facts and such an attitude toward truth that [all] can have a real chance to judge what the world is and what its greater minds have thought it might be.” [Midwest Journal, 2 no. 1:9-11 (Winter 1949).]

Du Bois points out how this banning or repression is a danger not just to individuals but to the country, because we lose “the right to think,” This repression dynamic is lethal to a society, undermining the freedom to learn even about views or information others might consider “dangerous”; undermining the legitimacy of all knowledges, and even of schooling and education. It propagates a worldview in which we are disinterested not only in learning but one another.

It also blocks our ability to resolve social conflicts. A key part of conflict resolution is knowing how to discern a “third way” and not only the “two sides” before you — also known as learning. We have to look very squarely and surely at the facts of what has happened, what is happening, what is being said and why — and remain committed to finding what it is that we do not yet know. Paradoxically, it’s in this fact-based new understanding that we often discover that third way, or what else could be.

When Charlie Rose asked Toni Morrison in a 1993 interview about whether white people, too, are harmed in the unfolding of white supremacism, she didn’t disagree. Instead, her face framed by glamorous waves of hair and a red lip, she flashed what she says is the more important question: “What are you, without racism?”

The statue of Brown in Kansas City, KS, has twice been vandalized. In 2018 racist graffiti and swastikas were painted on it. In November 2019, two of the fingers were broken off along with the marble scroll in the fingers held, a representation of the alternative constitution that Brown and others wrote.

Part of why I and others revere Brown is not only for the bravery of his life’s end, but that, as Frederick Douglass put it, he was “in sympathy, a black man… as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.” He lived and worked alongside Black people; he was, as W.E.B. Du Bois put it, “a companion to their daily life, knew their faults and virtues.” In 1849, antislavery novelist Richard Henry Dana met Brown and his family in North Elba, NY, and was shocked to find Brown matter-of-factly introducing white and Black residents equally. “The man was ‘Mr. Jefferson,’ and the woman ‘Mrs. Wait.’” Dana concludes, “[I]t was plain this family acted on principle in even the smallest matter.” Yet John Brown remains better known for his violence than his inviolable wish, that American society might renounce its covert war of “two nations”: White, and everyone else.

Read more

about John Brown