The Time My Mother Came Out to Me

My mother and I are in the back of an Uber leaving the Brooklyn Botanic Garden when she asks me about the difference between sex with men and sex with women. We are going to pick up my dog from the East Village apartment I lived in until a few weeks ago. The dog has spent the past few days with my ex-boyfriend of five years. Now, it is my turn to take her.

We are discussing my sex life—which is not totally off-limits but also not our usual conversation topic—because I need her advice about a friend I have recently started sleeping with. The first girl, as far as she knows, with whom I’ve been involved.

There is something middle-school-like about us having this conversation in hushed tones, glancing up every so often at the Uber driver. Like girls whispering in the back of a classroom. I giggle.

Then, she asks this question. About the difference between sex with men and women.

Quietly, I tell her what my experience is; it’s not the gender of the person that makes sex different, it’s the dynamic with that specific person. It’s not about body parts, it’s about vibes (my mom hates how often I use the word vibes).

When I was 19, my sophomore year of college, I came out to my parents as bisexual over FaceTime. I have never asked them if they guessed earlier—like when I was 12 and asked to be called Francesco and only wore boys clothes, down to my boxers, or when I was 16 and followed the Prop 8 rulings religiously and started a queer rights blog and became obsessed with Brokeback Mountain—but, at 19, I felt a bit pathetic for having waited so long.

My parents were fine when I told them, as I’d known they would be. I thought my mom seemed awkward—like she wanted to get off the phone. My dad asked a lot of questions and told me he loved me. And that was that. I started dating my college boyfriend a few years later, and for five years my queerness only surfaced in relation to my activism–volunteering for NYC Dyke March—and my interests—forcing my parents to watch A League of Their Own. But, now, with the end of my relationship, that was changing.

A few days after our Uber conversation, I was at my mom’s, where I was temporarily living, tutoring until late. When I came out of the laundry room—my sometimes-office—I was surprised to find my mom awake and sitting in an armchair. It was 10 p.m. I sat down on the couch opposite her.

My mother and I are extraordinarily close. Sometimes, I feel we are more like siblings than like parent and child. She goes to drinks with my friends; I go to drinks with hers. In Dublin especially, our friend groups merge into one shared bubble. Our ages no longer relevant, our relationship wiped of its power dynamic. Together, we talk about almost everything. I rehash the petty drama of my life for her, and she asks me for advice about siblings.

But, despite my mom and my closeness, when things get difficult, I stop being able to understand her. Like we are trying to communicate in different languages. More than anyone else in the world, she baffles me.

Since I graduated high school, our lives and interests have overlapped, leading us down parallel paths. She went back to grad school and studied Irish history, telling me over FaceTime or across the dinner table about the violence that her grandparents, my great-grandparents, had lived through. Those stories lingered in my subconscious, and when I began to write my first novel, it was about a mother whose past in Ireland is a secret to her daughter. As I wrote, my mom was writing too: a dissertation and then a short film called Trouble about our family’s history. A film I worked on with her, during long months in which we were either on fire or at each other’s throats. Through novel and thesis and film, we were both looking back at our family’s past. Both of us trying to understand ourselves, each other. Studying history in our different ways. Our lives like a conversation we were having. We have somehow navigated this shared interest, or obsession. We have somehow gotten closer through it, as opposed to pushing each other away.

Sitting across from her that night, I knew she wanted to tell me something. But I also knew that, more often than not, she does not say what she intends to. She opens her mouth to speak and then decides to say nothing at all. Or to make some oblique statement, trying to point me towards something lurking on the horizon which I cannot see. Once, she said there were three things she needed to tell me about her life. Ten years later, she still hadn’t told me what they were.

“What did you mean, the other day, when you said dynamic?” she asks me.

My mother is the youngest of eight siblings who grew up in various towns across the East Coast. They grew up without money, sometimes on food stamps, with a father who drank and grew volatile. They grew up chasing whatever jobs their parents could find, running from debts and, occasionally, the police. My mother got far away from that childhood. But that stuff doesn’t leave you. It stays on you like cigarette smoke. Like something stuck in your teeth.

I tell her what I meant by the word dynamic. I do not like talking about sex, but I do my best. It’s how you communicate with someone, I say. The gender doesn’t matter to me. This is not exactly true. Gender does matter—touches everything, especially sex—but it’s less because of the way anyone’s body functions and more because of how we experience and interpret gender. Because of who a man expects me to be in bed. Because of who certain women expect me, or don’t expect me, to be.

She says it, then, this thing she has been waiting to say. The thing she has been sitting here all night thinking about, pivoting back and forth in the swivel chair she’s sitting in.

“My first serious relationship was with a woman,” she says.

Hearing it, I do not know if I have always suspected it, or if it only clicks into place now. There are times I wondered—like when we were watching television and she mused, maybe everyone IS bisexual—but there are times I felt like my sexuality was a thing she would never understand. I remember again the moment I came out to her and how she seemed to sit in discomfort, not knowing what to say. How it felt like she did not care. Or, more truthfully, like she didn’t want to know. Like she was embarrassed.

The way she says it, I am sure that something went horribly wrong. She was 19, she tells me, the other woman was 29. I am expecting some tale of abuse, something that has always made my mother uncomfortable around these things. Some reason she never told me. But when I ask if it was bad, she says no. She says, “It was great.” And she begins to tell me about it.

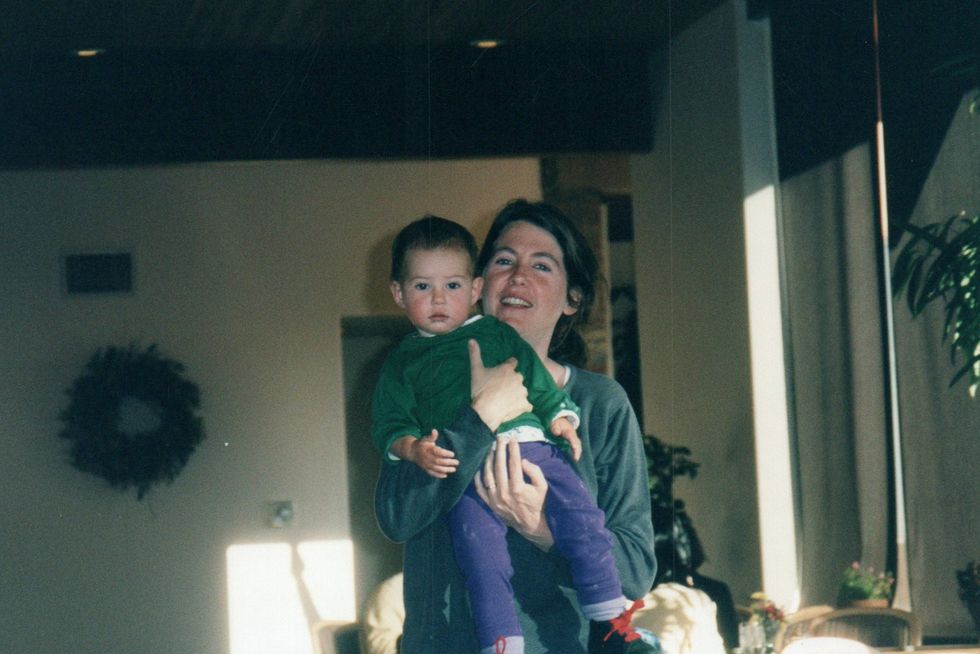

When I think of my mother, I think of meeting her eyes in the rearview mirror when we’d cross the Triboro bridge, and her saying, suddenly, “Do you want to go to Cape Cod?” and me wondering how she had read me like that when there were so many things she could not read, however hard she tried.

And so we would drive to Cape Cod, where she lived for some of her life, where my grandparents lived until they died. Pitch pines and air wet with rain. We went in winter and stayed short days, moist with my grandmother’s Lancôme lotion and the smell of my grandfather’s cigarettes and the whiskey he’d sworn he’d quit drinking years ago. I went with her out of some familial lust; even when I was most distracted, when my sister and my father pled excuses, I went with her. I suppose we forged something on those drives, or maybe it had already existed, and it was what forced me onward beside her, in the passenger seat.

I do not know why, but as my mother tells me about her first relationship, I begin to cry. Maybe it is because find myself suddenly angry, thinking of all the times I felt misaligned. The times, in high school, when I pulled my friends aside before they came over to my house and told them I wasn’t out to my parents. The times I, now out, stopped myself from saying something too revealing. But also the times when I doubted the fluidity of my sexuality. When I thought, again and again, that I could not like both men and women. That I must be confused, pretending in one way or another. A message never explicitly stated—except once by a college therapist—but absorbed into my bloodstream, nonetheless. My mom, I now know, could have stopped all of that. Or at least softened it. If I had known, from a young age, that she was like me. I might have felt differently—a lightness in my chest, a quieter voice in my head.

But there were other reasons I was crying, too. I was crying because I could hear the way my mother’s voice was wavering, a gymnast on a tightrope. Because she kept stopping, each pause heavy with what she was not saying. Because, when I asked her why she’d never told me, she said how at first she hadn’t wanted to interfere, hadn’t wanted to influence me, and then, how later, it had seemed like it was too late. It had seemed as if the person my sister and I saw was so defined, so set in stone as our mother, that to disrupt that image would have been terrifying. How do you tell your child you are not who they have always thought you were?

In short, she had had to come out to me, her child. The same way I had to come out to her. Both of us breaking the illusions the other had created. Both of us afraid of not being who the other thought we were. Both of us ashamed to say that we had lied. That we had not told the whole truth. That we might not be as close as we had pretended. As we had wanted to be.

Before I knew my mother was bisexual, I wrote a book about a mother and daughter. In it, the mother is hiding a past life, a terrible violence she committed, and the tragic story of her family. She has hidden so much of herself that her daughter does not even know her real name.

That idea, of a mother whose true identity is hidden from her child, is the story of all motherhood, to some extent. To be a child is to know only a sliver of the people your parents are. It is to know very little, often, about the people to whom, for a long time, you are closest. How could my mother and I have so much in common, share so much of our lives, yet know so little about each other? We are so close and yet, there will always be distance between us. Things lost as we try, and fail, to tell each other who we are.

“There’s one thing I wanted to tell you,” my mother says. “One thing I remember about that time.”

Her girlfriend had been a hard worker. She owned a house on the Cape with her ex, an idea that—at the time—my mother neither liked nor understood. She owned a car. She managed a restaurant. She was not butch, my mother says, putting air quote around the word, but people knew she was gay. Knew just by looking at her.

One day, she was driving home from visiting her mother. She got pulled over; the cop took one look at her and called for a tow truck. Her registration was expired, but she knew why he was giving her a hard time. This was the ’80s outside Boston. He drove her to a payphone in his car, her sitting terrified in the passenger seat. She called my mom, who borrowed her sister’s car and drove to pick her up. By the time my mom got there, she had been waiting two hours on the side of the highway.

My mother’s girlfriend was not the type to get angry, to lose her temper. But when my mother picked her up, she was furious, shaking from the confrontation with the cop.

“There was a saucepan on the floor of the passenger seat,” my mom says.

“A saucepan?”

She laughs. “Yes,” she says. “I don’t know why.” Her mouth twists.

And so my mother’s girlfriend picked up the saucepan, and she began to smash it against the dashboard. Again and again, with all her force, she hit and hit and hit. Until my mom thought something was going to break.

“I’d never seen someone angry in that way,” she says. And my mother grew up with angry. “It was focused. Real anger. I didn’t fully understand it then. But later, I understood how it must feel. How it must wear you down and wear you down.”

In my novel, when the mother realizes that her daughter also has secrets, she does not want to see them. She tries to look away from who her daughter has become, the things she has done. They have both lost something: the versions of each other they clung to. It is something to be mourned, that loss.

But that bond does not break. In the end, there is a lot of blood. And there her mother is, holding a washcloth to her forehead, changing her clothes. There her mother is to protect her. Whoever she is: a stranger, a best friend. Or both at the same time.

Francesca McDonnell Capossela is a queer writer and Irish American dual citizen. She grew up in Brooklyn and holds a Master’s in creative writing from Trinity College Dublin. Her writing can be found in the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Point, Banshee, The Cormorant, Columbia Journal, Guesthouse, and the anthologies Dark Matter Presents Human Monsters and Teaching Nabokov’s Lolita in the #MeToo Era. Her debut novel, Trouble the Living is out now. Francesca lives on the Lower East Side of Manhattan with her dog Lyra. For more information, visit francescamcdonnell.com.