“They don’t realize how deeply racial bias permeates”: Central Park birder on where liberals fail

Trauma, heartbreak and letdowns are things we all experience, regardless of your background, ethnicity or where you come from. Often, people dealing with pain are taught to directly address the problem. For writer Christian Cooper, developing a pleasant distraction in nature that forces him to be present, is healing and freeing. He shared with me the many ways in which birding has been an outlet for nearly all his entire life.

“I started birding when I was about 10. I knew I was gay when I was about five. That was a hard place to be back in the 1970s,” he said on “Salon Talks.” “One of the things that birding does is that it gets you outside of yourself. That was important to me as a kid when I was a queer, nerdy, closeted kid.”

He went on to become a Harvard graduate and one of the first openly gay employees at Marvel Comics, who led the fight for inclusion by introducing the first gay storylines and the first gay male character in “Star Trek, “Yoshi Mishima, in the Starfleet Academy comic series. But the world didn’t get to know him and his gifts until his favorite hobby directly collided with America’s fractured relationship with race and bias.

On May 25, 2020, the same day that George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis by a police officer, Christian was doing what he does most mornings before much of New York City is awake – watching birds through his binoculars in Central Park. It was there where he encountered Amy Cooper, who had let her dog off leash. Leashes are required in the bird-watching area of the park, so Christian reminded Amy to follow the rules. She refused, and Christian, determined to not scare the birds he came to watch, offered Amy’s dog a treat to de-escalate the situation. Amy called the police and lied, “There is an African American man – I am in Central Park –he is recording me and threatening myself and my dog. Please, send the cops immediately!”

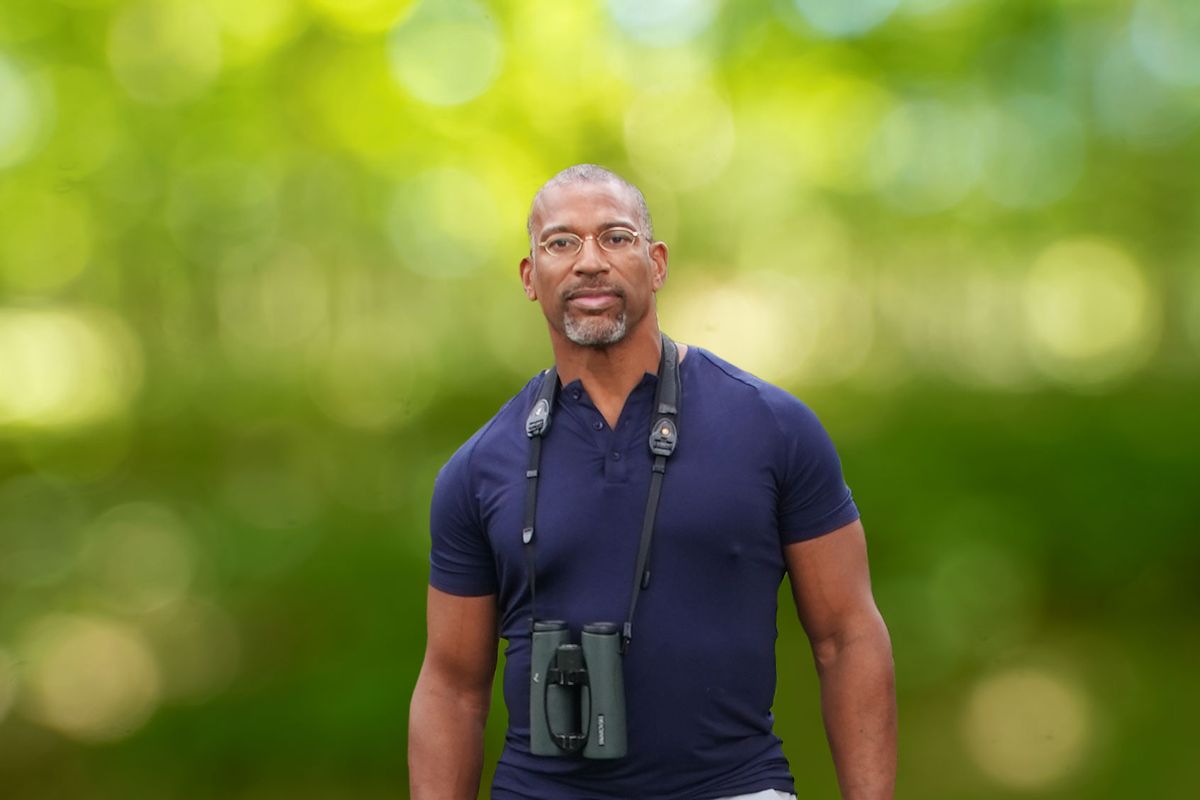

A video of this encounter went viral, exposing Amy, and the uncomfortable history of how white people have purposely weaponized police officers for their own convenience. Now, Christian has thousands of fans, an exciting travel television show on Nat Geo Wild called “Extraordinary Birder” and a new memoir, “Better Living Through Birding.”

Watch my “Salon Talks” episode with Christian Cooper here or read a Q&A of our conversation below to hear him reflect on that day in Central Park, why we need to keep having tough conversations about race, and the bird he’s been chasing for years but still hasn’t seen.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

One of the things I was thinking about when I first heard about the show is I wonder if you can still go to Central Park and bird without people running up to you for pictures and scaring the birds away because they want to get that selfie.

Well, one of the things you have to remember is I tend to go very, very early before most people are awake, so that helps.

Then sometimes people come up and sometimes it’s the New York thing, because in New York we tend not to acknowledge celebrity. It’s part of our thing. You may notice that Jake Gyllenhaal just walked by you, but you don’t do anything about it. You just maybe smile a little. But then sometimes people come up and say something and it’s always very nice and it’s always very welcome and it’s a nice thing.

For a person who has never considered birding, could you talk about some different ways they can discover themselves through birding?

One of the things that birding does is that it gets you outside of yourself. That was important to me as a kid when I was a queer, nerdy, closeted kid. I started birding when I was about 10. I knew I was gay when I was about five, so all this is going on. That was a hard place to be back in the 1970s.

“As you focus outward, all those other things just kind of fall away, at least for a little while.”

When you’re birding, you can’t be in your own head. You can’t be worrying about whatever your worries are. Whatever is getting you down or preoccupying you, you can’t be thinking about that when you’re birding. You’ve got to be focused on, okay, I’ve got to be alert to a certain kind of motion, or I’ve got to be listening for sounds that’ll tell me where to focus. As you focus outward, all those other things just kind of fall away, at least for a little while and you’re connecting with the larger world beyond you. That is incredibly healing and it makes you feel connected to something much bigger.

It forces you to be in the present.

Yeah, forces you very much to be in the present and outside of yourself to recognize that, OK, there’s all this stuff, but there’s all that stuff. Birding, I think because you’ve got to be focused on sight and sound, I’ve got to pay attention or I’m not going to see any birds, that gets you focused, so that’s a wonderful thing that birding can do for anybody.

If you’ve never done it, it’s open, it’s accessible to everybody. I don’t care if you’re in a wheelchair and you’re homebound, you can go to your window and you can look out your window and see what birds come to your fire escape or to your backyard or whatever you’ve got.

So you can bird anywhere.

You can bird anywhere.

As I was reading your book, and I’d take breaks to run errands, take my daughter to school and things like that, I was looking around because in Baltimore I feel like I just keep seeing the same bird over and over again, but I’m probably not looking close enough.

Well, you’ll be amazed. I mean, lots of people walk through Central Park and they’re like, “New York City is just pigeons,” and they have no idea what is going on around them, particularly during migration when birds funnel through Central Park in hordes. And they just don’t know, they don’t realize.

It’s funny because the pandemic did that. There’s a lot of what we call pandemic birders, people who started birding during the COVID era. It’s wonderful that all these people have found birding, but when we run into them, so often they say, “I’ve been in Central Park for years and I had no idea until I started birding that all this was going on.” And now they’re hooked.

It’s always beautiful when you can just discover different things about your own space when you pay closer attention. I think that’s excellent. And it’s why I think so many people will enjoy your show, right?

I hope so, yes.

I’ve only had the luxury of watching a couple of episodes and I hope a lot of people tune in. People don’t realize how intense it is. When I saw a bird being put to sleep to test his fertility, my mind was blown.

Yeah, mine too. I hope that comes across.

Can you talk about that procedure?

There’s what we call an endemic bird, a bird found only in this one place. It’s called the iguaca. It’s a native Puerto Rican parrot. The Puerto Ricans are trying desperately to save it because they’ve been hit with hurricanes and deforestation and so many things that have made it very hard for this parrot to survive.

“In North America, in my lifetime, since I started birding, we have lost one third of the birds in North America.”

One of the things that’s making it hard for the parrot to survive is these parrots have a fertility issue. The parrot has almost become a symbol of Puerto Ricans and their tenacity and their determination to make their island work despite all the setbacks, despite all the hurricanes, so to help the parrot survive, one of the things they’re doing is they’re making sure that the males have got a good pair on them to make another set of babies. To do that, you’ve got to look inside the bird. So they send this little tiny microscope inside the bird, and you’re peering past air sacs to look at the testicles of an iguaca to see if this guy has a healthy pair of testicles.

We can test for fertility, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that this animal is going to reproduce. There are so many issues with extinction going on. Unfortunately, you haven’t seen the Hawaii episode, but that’s huge in the Hawaii episode. Hawaii has lost three quarters of their native birds. They’ve gone extinct already. That’s for a variety of factors all having to do with westerners having come to Hawaii and brought invasive species like cats and diseases, so it’s a mess over there in Hawaii.

Westerners mess up everything.

There you go. But again, for the Hawaiians, these animals are part of their mythology and they want to save them, so they are fighting tooth and nail. That’s what the title of the show “Extraordinary Birder” refers to, not to me, but to the biologists and just regular old birders who have dedicated themselves to protecting these birds and saving them and bringing them back. For example, in Hawaii, some of the people I met who are moving mountains to try to save the birds they have, are just so inspiring.

We do still have to worry about extinction very much so, especially in an era of climate change, because birds are our best indicator of climate change. The old metaphor of canary in a coal mine, there’s a reason why people say that. It’s because they would take the canary down to the coal mine. It would die from the fumes first, letting people know [it’s] time to get out of here.

Well, the birds are our best indicator. They are everywhere. They are visible, they are accessible to us, and they are trying to tell us something, because here in North America, in my lifetime, since I started birding, we have lost one-third of the birds in North America.

“Do what our ancestors shed blood for and vote.”

Now I’m talking about numbers. For example, if there were three billion birds in 1970, there are now two billion birds. One billion birds, just gone. That’s trying to tell us something. Extinction is very much an issue.

The birds are trying to tell us, “Take care of your environment. Do something about climate change.” That’s on all of us to actually do something about it. We can’t wait for the government. Yes, it’s their job, but if we wait for the government to do it, we’ll all be dead, so it’s on all of us to take on the responsibility of doing something about climate change.

Has there ever been a bird that you’ve wanted to see and you just never caught it?

Oh, sure, sure. We call that your holy grail bird. Where you’re sort of hoping to see it one day, but you still haven’t seen it. Another word for it is your nemesis bird, if there’s a bird you’ve been trying to see and you keep missing it. For me, it’s probably a bird called a gyrfalcon. It’s the biggest falcon in the world, and it’s a bird of the foreign north. But every once in a while, one comes down south to New York, and when it has, I’ve chased it on Long Island, I’ve chased it in Westchester, hoping to see it. Both times it got away. I missed it.

Have any of your friends caught it?

Yeah, some of my friends have seen it.

Now, do they just look at it or do they snap pictures too?

Depends on the person. A lot more people these days are snapping pictures because the technology has gotten better, lighter, cheaper, easier to use. But I’m old school. I like to be in the moment and focus on the experience, so I still use a pair of binoculars. Some people carry both. Some people these days just use a camera. It really depends on how you bird.

I write memoir and I teach memoir too. When a lot of people decide to get into this genre, they want to stay on the outside of a story. They don’t really want to go deep into it. I think you went deep and there were some beautiful transformations throughout the course of the book. Was it difficult for you to put out?

Sure, because I’m not a very confessional person. Since you’ve read the book, you know I sort of pride myself on having, to use a Star Trek reference, a very Vulcan demeanor. I don’t like to act on emotion. I like to keep emotion on the inside, and yet I’m supposed to write a memoir. You got to put it all out there.

My editors were fabulous about that because there would be times when I’d sort of put something in very clinical Vulcan terms about what was happening, and they’d be like, “No, no, no, we need you to go back in that a little bit more deeply.” And I’m like, “No.” And they’re like, “Yes.” And I’m like, “No.” They’re like, “Yes.”

“You’re not just going to blow past this moment.”

Exactly. They were very good about that. Particularly when I started writing about family and when my family members, my mother, father, grandmother start dying off, that was really hard to write. I mean, that was very hard, so it took a while and I had to sort of knuckle down, but I wanted to put something honest on the page.

What frustrated me about the book, and I would love to hear your take on this, is I’m like, wow, this guy was a revolutionary person at Marvel, played a role in introducing the first gay character. Northstar?

Northstar.

Northstar, and then on “Star Trek” as well.

And then on “Star Trek.” Yeah, my role in Northstar was very minimal. I was the assistant editor on the issue of that comic book.

I mean, but still you were that voice in the room.

Sure, yeah.

You were that voice in the room as a Black man, as a gay man, as a person who loves comics and who knew that millions of people all over the world who can be inspired by that. So you had that in you.

You went to Harvard, which is an amazing accomplishment and you are a fascinating person. So I’m thinking, “Wow, how come I need some goofy lady in the park with her dog before I hear about this guy?” I’m like, “This is the biggest problem with our system because the bird show should have been out years ago.”

That’s true for so many people. I don’t look at it that way. I look at it the other way. I am incredibly privileged to be able to tell my story in my own words and have so many people read it, but there are so many people doing so many amazing things, again, I’ve met them working on the show, who contribute so many things to the world in big and small ways. Their story very often doesn’t get told.

“The point is not her. The point is the racial bias.”

All the things I’ve done in my life, I didn’t do them so that I could eventually write a memoir. I just did them because that’s what I do. The good thing about what happened with the incident is that it opened up some doors for me so that what I have always been doing, I now get to keep doing but on a bigger platform so it reaches more people.

I almost feel like how many people are being cheated out of meeting or understanding or learning about a Christian Cooper because a network or a publishing company or our greater society doesn’t see value in showing the dynamics or the multiple beauties that exist inside of a person until something bad happens. It frustrates me so much.

I hear that. I will share your frustration in terms of sort of our culture’s obsession with celebrity for stupid reasons. I mean, I didn’t even know what a Kardashian was for umpteen years, and I led a blessed existence until someone finally, I said, “What’s a Kardashian?” They looked at me like I had three heads. And sadly, now I know.

But that’s the kind of thing that our culture exalts these days. There are so many people doing amazing things. That’s one of the things I love about the show, is I get to take some of those people and put what they’re doing in front of the camera so that people know.

There’s a blind birder in Puerto Rico, so that highlights for people you don’t even have to be sighted. You can be blind and you can be a birder. That’s one reason why we say birder instead of bird watcher. This guy birds solely by ear, this guy in the Rockaways who took it upon himself just as a volunteer to save the piping plover out in the Rockaways. And he’s organized dozens of volunteers to do that. That’s amazing. So I get to tell his story. In our own ways we can correct that. We can push forward the stories of people who are doing amazing things.

You having the opportunity to talk about birding and to open it up to all of these different people is a way of moving the conversation forward. Sometimes I wonder, does that put us in a better place in having the conversation around race and race relations and how these things affect people?

I think it added to the conversation, and I think it added something that was necessary to the conversation. I think, and I always say this over and over again, that incident was not about her. It was about the racial bias that it revealed and how for a lot of, particularly white people, because we as Black people know, we’ve experienced it, but a lot of people were clueless. They’re like, “Ah, Obama was elected president. We’re all good now.”

They don’t realize just how deeply racial bias permeates our culture, and yet here it was for everybody to see in a city as liberal as New York with someone who didn’t use any slur but used the correct term African American and yet still this racial bias.

“Don’t be distracted by her. Focus on the bias and how it bubbles up in these horrible ways that we can do something about.”

The point is not her. The point is the racial bias. I think bringing that racial bias, letting people understand that it’s there was important, particularly because it bubbles up in ways that are far more important in our society as evidenced later that same day when that racial bias made a police officer in Minneapolis, a white police officer, think it was okay for him to kneel on the neck of a Black man until that man was dead. And for three other officers or four, I forget how many, to stand around and not do anything as he did that. That’s the racial bias. That’s what we have to fight against.

The racial bias that percolates up, and the fact that Washington D.C., urban, largely Black and brown population has no representation, no voting representation in our political system in Congress, and yet you go to rural, mostly white Wyoming with fewer people than Washington D.C., you go to rural, mostly white Vermont with fewer people than Washington D.C., and they both have two senators each in the Senate. But nobody is doing anything for statehood for Washington D.C. Why is that? That’s the racial bias at work. That’s the racial bias we should focus on. Those are the things we can change. We should keep our eye on the prize. Don’t be distracted by her. Focus on the bias and how it bubbles up in these horrible ways that we can do something about.

Absolutely. I feel like I’m at a place in my career where I’m sick of talking about race. I’m sick of talking about it. I’m sick of having the conversations. I’m sick of the hot take on whatever just happened. But then the other part of me is like, “How do we move the ball forward if we’re not having these conversations?” And then you kind of get into this space where, is it going to do anything? It gets difficult.

The thing for me, because I think a lot of us feel that, when I start to feel I am sick of talking about this, I do something. Doing something instead of talking is such a great antidote.

I was out in Freeport, New York a month ago, registering voters out there because Long Island could go red, could go blue, and it could make the difference with who controls the House. We control who controls the house, that determines who will vote to make Washington D.C. a state, things like that.

There are things we can do as individuals, instead of talking. First and foremost, do what our ancestors shed blood for and vote. But voting is not enough. Get your friends to vote, register other people to vote. All of this stuff, we can do as individuals. I find when I get sick of talking, doing just makes me feel so much better.

“Extraordinary Birder with Christian Cooper” is streaming on Disney+.

Watch more

“Salon Talks” with D. Watkins