There’s no such thing as a conservative intellectual — only apologists for right-wing power

In 1950, author and critic Lionel Trilling wrote:

In the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition. For it is the plain fact that nowadays there are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circulation. This does not mean, of course, that there is no impulse to conservatism or to reaction. Such impulses are certainly very strong, perhaps even stronger than most of us know. But the conservative impulse and the reactionary impulse do not, with some isolated and some ecclesiastical exceptions, express themselves in ideas but only in action or in irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas.

Three-quarters of a century later, Trilling’s statement remains broadly true, as a glance at conservative books will attest. The hundreds of conservative book titles that have geysered out of Regnery, Broadside and other right-wing imprints in recent years are almost invariably distinguished by their numbing sameness: a shrill cry of victimhood, a hunt for scapegoats, a tone that alternates between hysteria and heavy sarcasm, and a recipe for salvation cribbed from Republican National Committee talking points and Heritage Foundation issue briefs. The fact that they sometimes hit the bestseller list is principally due to the well-funded conservative media-entertainment complex’s bulk-purchase scam.

The vast majority of these efforts are the products of political operatives, talk-show entertainers and the ghostwriters for hack politicians eyeing a presidential run. What is chiefly distinguishable about the output of self-styled conservative intellectuals is that their academic credentials and scholarly pretensions often gain them reviews in the prestige media, presumably on the basis of their importance. This month, the New York Times reviewed “Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future,” by Patrick J. Deneen, a lecturer at Notre Dame.

Before even attempting to evaluate the book in the context of present-day issues, we’d better be clear on what American conservatism is, where it came from, who the people are who purport to be conservative intellectuals, and what their game is.

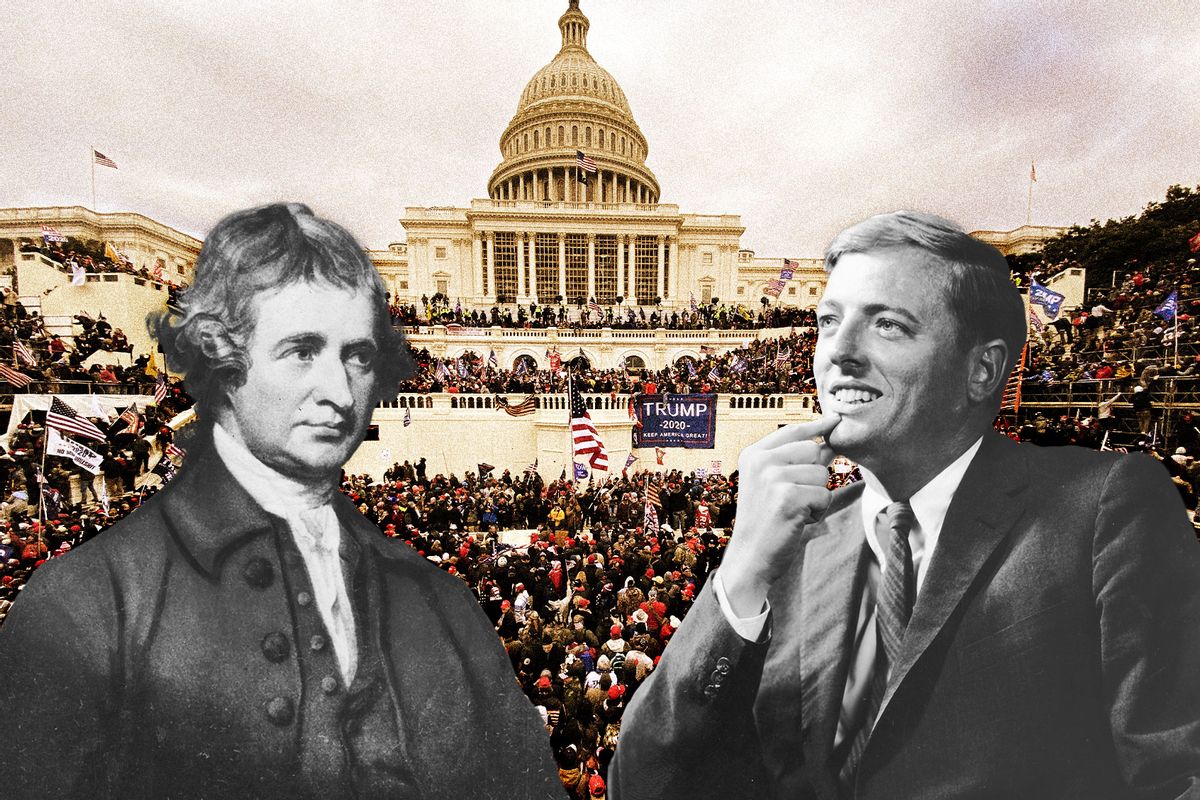

In Europe and America, conservatism as we now know it grew out of the reaction to the French Revolution. The Anglo-Irish 18th-century statesman Edmund Burke is typically held up as the spokesman for the enduring conservative sensibility, and such prominent postwar American conservatives as William F. Buckley Jr., Russell Kirk and George Will have made much of Burke’s purported moderation and good sense.

Conservative “bestsellers” are almost invariably distinguished by their numbing sameness: a shrill cry of victimhood, a hunt for scapegoats, a tone that alternates between hysteria and heavy sarcasm.

Among Burke’s epigrams are such copybook maxims as “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” Uplifting stuff. But political theorist Corey Robin, in “The Reactionary Mind,” thinks these words from the younger Burke do not represent what he was to become. Robin sees darker currents in a Burke who understood Jacobin violence as implicit in every attempt at political reform. Toward the end of his life, Burke harped on the “subordination” of the masses to the classes as imperative for any sort of political order.

On the other side of the English Channel, the reaction against the French Revolution packed a lot more blood and thunder. Joseph de Maistre, a diplomat from the Duchy of Savoy, did not trim his sails. He considered the executioner to be the indispensable backstop of civilization, the better to save wayward souls: “Man cannot be wicked without being evil, nor evil without being degraded, nor degraded without being punished, nor punished without being guilty. In short … there is nothing so intrinsically plausible as the theory of original sin.”

Émile Faguet, a French author and critic, called Maistre “a fierce absolutist, a furious theocrat, an intransigent legitimist, apostle of a monstrous trinity composed of pope, king and hangman, always and everywhere the champion of the hardest, narrowest and most inflexible dogmatism, a dark figure out of the Middle Ages, part learned doctor, part inquisitor, part executioner.” And something of a sadist, to read his musings.

Maistre, though lesser known than Burke, embodies the essential points of the present conservative mind at a deeper level than taxes, spending or size of government. Isaiah Berlin, the great historian of western ideas, considered Maistre the true father of reactionary western conservatism, and, indeed, a precursor to the past century’s fascist movements.

However much modern theorists have elaborated upon the ideas inherent in conservatism during the two centuries since Maistre, they all seem to me to boil down to three simple points:

- A desire for hierarchy and human inequality. This belief derives from the medieval religious notion of the Great Chain of Being, whereby there is a place for everybody and everybody must know his place. It justifies economic exploitation and denial of political rights. Conservative writers propagandize on its behalf with a straw-man argument: Any gain in equality costs society an equal or greater loss in freedom; egalitarianism is the mere soulless equality of the gulag, where we cannot own property and must share toothbrushes. This sentiment pops up consistently in the works of American conservative theorists, from Buckley’s “Unless you have freedom to be unequal, there is no such thing as freedom,” to David Brooks’ hankering for rule by a wise elite. American-style laissez-faire economics and libertarianism are largely based on this idea.

- The only acceptable society is based on Christianity. Never mind the establishment clause of the First Amendment; conservatives will forever try to smuggle in more and more official endorsement of religion until the United States is effectively a theocracy. The rationale is that some sort of divine or transcendental dispensation is the sole basis for a just temporal order. Translated into the bumper-sticker mentality of American Christian fundamentalism, that means that if people don’t believe in God, there’s nothing to stop them from running amok and killing people. This thesis would have been news to medieval crusaders, the Holy Inquisition, Francisco Franco’s Falangists or the Russian Archbishop Kyrill, who has blessed Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting carnage.

- We must obey tradition. For some unexplained reason, our ancestors were infinitely wiser than us, and apparently they get a vote on present affairs. To paraphrase Edmund Burke, if we’re going to have democracy, let’s extend it to the dead. Scratch someone who fancies himself an educated conservative and you will often find a person who reveres the past; unfortunately they leave out details like slavery, witch burning and childbed fever. Many psychologists consider this mentality to be a cognitive bias in brain function, but whatever its source, the political utility of the attitude is obvious: Utopia only exists in an ever-receding past, progress is impossible, and future generations shall profess bygone superstitions. And tradition, in this case, means the folkways of a specific, favored culture, thus denying the universality of the human spirit. The idea is well expressed by Buckley’s statement that conservatives must “stand athwart history yelling ‘stop.'”

Joseph de Maistre was “a fierce absolutist, a furious theocrat, an intransigent legitimist … always and everywhere the champion of the hardest, narrowest and most inflexible dogmatism.” All the essential points of the present conservative mind.

One can grasp that the three precepts dovetail together in that they all rely on dogmatic assertion, denial of a scientific or empirical basis of reality and reactionary nostalgia. They are also pretty thin gruel for founding an intellectual tradition: there are simply too many departments of knowledge, for instance, much of science, that must be declared off limits to prevent them from tainting the party line. This is why conservatives habitually retreat into mysticism, gut feelings and the wisdom of our fathers when the facts are against them. It is more accurate to say that conservatism is a counter-intellectual activity that sometimes employs the trappings of intellectual discourse.

Conservative theorizing on politics, civil society or ethics and morals is very likely derived from one or more of these three axiomatic rules. A notable example is Michael Oakeshott, a British conservative much esteemed by Buckley, Andrew Sullivan and other figures in the conservative movement for his suggestion that rationalism in politics ultimately leads to police states and concentration camps.

Oakeshott, who was far less dogmatic than his later acolytes, took a grain of truth and exaggerated it. Marxist-Leninists, who claimed to have discovered laws of historical development that were as unimpeachable as the laws of physics, tried to impose their “scientific” vision on society with horrible results. Oakeshott was horrified by this, and was also disturbed by the postwar British welfare state; this was the impetus for his denunciation of political rationalism. Here we see the classic slippery-slope argument: Although any thinking adult in the mid-20th century would have had cause to fear the statism of the Nazi or Soviet type, it is hard to envision Britain’s National Health Service as the embryo of jack-booted totalitarianism.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Is it not true that taking a rationalist position on the desirability of clean drinking water or public hospitals or eradicating measles is the correct position, demonstrable not only for its practical results but for its humane intent? In the hands of American conservatives, the entire Oakeshottian argument has degenerated into assertions that a proposal for end-of-life counseling in the Affordable Care Act leads in a straight line to forced euthanasia, or that vaccines are a government plot to implant microchips.

Oakeshott was best known for the following statement: “To be conservative, then, is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.”

The difficulty with his statement, apart from the fact that it is the kind of self-satisfied homily that Laertes might have inflicted on the Court of Denmark, is that it idealizes a psychological disposition the exact opposite of that possessed by modern conservatives. They are hag-ridden by demons — the fallen state of man, the hopeless decadence of secular humanism, the imminent collapse of Western Civilization (a term always capitalized). They are radical rather than pragmatic, undeterred by the mountain of evidence that tax cuts don’t increase revenue, an unregulated market is not stable, and banning abortion won’t make people more moral. They crave power, are as humorless as a commissar, and entirely lack introspection as to their own fallibility.

Who are the people whom the American prestige media have dubbed conservative intellectuals? Post-World War II America has produced several definable varieties of conservative apologist; for the sake of simplicity, they can be reduced to three broad categories: econcons, neocons, and theocons.

Modern conservatives are hag-ridden by demons — the fallen state of man, the hopeless decadence of secular humanism, the imminent collapse of Western Civilization (a term always capitalized).

Virtually all economic conservatives trace their origin story to the Austrian-born Friedrich Hayek’s 1944 work, “The Road to Serfdom.” Like Oakeshott, Hayek saw economic centralization as a crucial element in the formation of the mid-20th century totalitarian states. He warned that if the Western democracies adopted economic planning and welfare states, they would insensibly lurch down the slippery slope towards tyranny.

It was not an unreasonable fear at the time; however, virtually all experience in the established democracies since then has refuted his thesis: High levels of taxation and spending, prudent amounts of economic planning (as in France during les Trente Glorieuses) and comprehensive welfare states, as in Scandinavia, are entirely consistent with personal freedom, broadly shared prosperity and high levels of social trust.

Rather than recognize that reality, economic conservatives doubled down to the point where they were no longer followers of Hayek (who indeed wrote an essay titled, “Why I Am Not a Conservative“) and became de facto acolytes of Ayn Rand, the author of unreadable potboilers who transformed selfishness and misanthropy into a cult religion with herself as its chief deity. Libertarian crackpot Ron Paul even named his offspring, today a senator from Kentucky, after the goddess of greed. Paul Ryan, the former House speaker, supposedly required his interns to read “Atlas Shrugged”; one would have thought the constitutional provision against cruel and unusual punishment would have banned this Sisyphean labor.

The influence of the econcons peaked in the late 1970s with Milton Friedman’s monetarism and Arthur Laffer’s curve. The exploding deficits of the Reagan administration demonstrated that most conservative politicians and their operatives didn’t really care about economic orthodoxy except as campaign fodder and a stick to beat Democrats. Profligate spending is fine as long as it benefits political donors and not society at large. The present Republican Party is almost indifferent to economic issues (except when hostages need to be taken, as in the debt limit follies, or when the donor class demands another tax cut); it has mostly forsaken economic theories for the more emotional demagoguery of the culture wars, as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has demonstrated in his jihad against a formerly sacrosanct corporation, Disney.

The econcons were displaced by the neoconservatives, a largely New York-centric group revolving around the Norman Podhoretz-Irving Kristol axis that in the late 1970s threw off their early Democratic Party (or even socialist) affiliations and opted for the GOP. They became the pet intellectuals of presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, administrations otherwise sorely wanting in cerebral credentials.

Neocons became notorious as tub-thumpers for a militarized, global American imperialism that was nevertheless supposed to be benign because its intentions were pure (so much for Oakeshott’s preferring the limited to the unbounded). Sniffing publicity, even the boozy Trotskyite intellectual-cum-gadfly Christopher Hitchens became a neocon long enough to cheerlead the Iraq war and endorse Bush’s re-election. We don’t hear much from the neocons anymore, partly owing to mortality but mainly because the epic disaster of the Iraq invasion and its reverberating consequences discredited them as thoroughly as is possible in America, the fabled land of second and third chances.

We don’t hear much from the neocons anymore, mainly because the epic disaster of the Iraq invasion discredited them as thoroughly as is possible in America, the fabled land of second and third chances.

Indeed, the sheer, agonizing catastrophe of Iraq in its conception and execution is a lesson of world-historical magnitude about the astounding incompetence of American conservatives in running a complex operation, or in positive governance more generally. We have seen this pattern play out in everything from the Trump administration’s handling of the COVID pandemic to the Texas state government’s management of its power grid. After all, when an authoritarian controls the administrative levers of state, all he typically needs to do to overthrow democracy is to throw the switch. Ironically, it was only the gross ineptitude of Trump and his lackeys that saved us from banana-republic status. Such is the quality of conservative ideas.

Around the time of Barack Obama’s election, the neocon wave receded before the incoming tide of theocons, a group of religious polemicists always prominent in post-World War II conservatism and becoming dominant as the Republican Party transformed itself into the electoral arm of Christian fundamentalism. The theocons have always leaned heavily in a specific sectarian direction that is at first sight counterintuitive.

The largest and possibly most cohesive voting bloc in the GOP consists of evangelical Protestants. This is natural for an increasingly xenophobic party, given that evangelicals skew more strongly as old-stock Americans compared to the more heavily ethnic Catholics. As recently as 1960, there was talk among evangelicals that a Catholic should not be president because his ultimate loyalty might be to Rome rather than the Constitution.

Yet throughout this period, there has been no evangelical equivalent of Sam Alito or Antonin Scalia on the Supreme Court, and the most prominent theoconservative intellectuals since Buckley launched postwar conservatism have been Roman Catholics. George W. Bush, who wore his Methodism on his sleeve, appointed two Catholics to the Supreme Court and salted his advisory boards with lay and ordained Catholic theologians like Richard Neuhaus, a pure example of the species. (Bush made him an adviser on stem cell research, despite Neuhaus’s absence of biomedical credentials. He even gave theological blessing to preemptive war; in promoting the Iraq disaster, Neuhaus’ bilious sanctimony ironically echoed that of the professional atheist Hitchens, perhaps proving the horseshoe theory of ideological extremism).

Why do we see this paradox, with so many Catholics leading a predominantly Protestant ideological movement? In America, the religion of Luther, Zwingli and Calvin has, in its fundamentalist interpretation, taken a turn so unrelentingly hostile to intellectual activity that it has rejected much of the last century and a half of settled science. A fundamentalist evangelical intellectual is a walking contradiction, indeed a suspected subversive among his coreligionists. For details, behold the Southern Baptist Convention.

Under the circumstances, the conservative movement has been obliged to use Catholic ideologues as its public idea men (they are invariably men) and interpreters of the Constitution. Given that the Catholic tradition has always made a show of scholarly erudition, and that Jesuitical training has its advantages in the cut-and-thrust of debate, Catholic apologists have won the conservative idea war by default.

People who now call themselves Catholic intellectuals are almost always medievalists, waxing nostalgic about a (wholly imaginary) pre-Reformation Europe that was pious, organically unified and energized by the One True Faith.

Chauvinistic Catholics were prominent in Buckley’s founding of postwar conservatism; he made great efforts to ensure everyone knew he followed the Church of Rome. His National Review co-founder and coauthor of a defense of Joseph McCarthy, L. Brent Bozell, even outdid Buckley in that department, being as ferocious a theocrat as Maistre had been more than a century earlier. Bozell was instrumental in turning abortion into the biggest culture-war issue of the last 50 years, and eventually came to repudiate the entire constitutional basis of the United States — the founders, he believed, had not bequeathed us a godly government.

From Bozell and his leading contemporaries like Russell Kirk (who added the zeal of the Catholic convert and is now the patron saint of Hillsdale College) down to present-day apologists like George Weigel (longtime defender of the Rev. Marcial Maciel, founder of the Legion of Christ and a notorious child abuser), the theocons have never reconciled themselves with the fundamental nature of the American state at its inception. The Constitution, with all its good and bad features, was a pluralistic framework that attempted to resolve the conflict among diverse interests with separation of powers, federalism and consensus by compromise. The founders, conscious of the perpetual religious wars of Europe, declared the federal government off limits to control by any religious sect.

People who now call themselves Catholic intellectuals are almost always medievalists, waxing nostalgic about a (wholly imaginary) pre-Reformation Europe that was pious, organically unified and energized by the One True Faith. The medieval mindset brings other baggage as well: discomfort with liberal, secular democracy (Bozell decamped to Franco’s Spain, because “you breathed the Catholic thing there,” along with breathing the fascism); Kirk’s belief that society requires orders and classes that emphasize “natural” distinctions (no doubt derived from the Great Chain of Being but equally applicable to white supremacy or the subordination of women); and a mystical reverence for tradition rather than empirical method.

There is also the unmistakable note of persecution complex in the theocons’ argument, a subspecies of what political scientist Richard Hofstadter called “the paranoid style in American politics.” They are forever standing on the battlements of Christendom or Western Civilization, resisting nobly but perhaps futilely the onslaught of barbarians, heretics and secular humanists. The very aggressiveness with which the American religious right engages in bare-knuckle politics is a psychological projection of its feeling of righteous martyrdom, its precious faith in constant peril of being banned by a supposedly overbearing liberal culture.

Theoconservatism is now the dominant and possibly the only significant strain of American conservatism with intellectual pretensions. But for all the affected tossing-about of references to Aristotle or Aquinas, the regurgitation Latin phrases like an English schoolboy at Eton, and the scholarly pose of the theologian, it is not opposed to the intransigent anti-intellectual stance of present-day conservatism as a whole — nor does it offer any meaningful critique of the Trump phenomenon. (One honorable exception is Peter Wehner, who served as a theocon speechwriter for three Republican presidents but has been witheringly critical of Trump.)

Patrick Deneen’s latest book is yet another reiteration of theoconservative complaints of the last 70 years, and adds one revealing twist. It takes up where his 2018 book, “Why Liberalism Failed,” left off. That book offered the usual catalog of the alleged failures of liberalism. Coming as it did at a time when Democrats’ political morale was at low ebb, one has to assume its favorable reception in unlikely circles was due to its uncharacteristic condemnation of things like economic distress in the heartland and environmental destruction. The book even garnered an endorsement from Barack Obama.

Patrick Deneen at least tells us what he desires: the “overthrow of a corrupt and corrupting liberal ruling class” and its replacement with a new elite, his elite, that would rule through “raw assertion of political power.”

A few seconds’ thought might have triggered a more critical take. Has any conservative in public office during recent decades ever seen a proposal for environmental protection that he didn’t hate? How many Republicans have resisted their party’s efforts to deny Medicaid or food stamps to struggling Americans, or to oppose minimum wage increases? Yet in Deneen’s bill of indictment, the social consequences of Republican policies were somehow the fault of liberals. Obama’s promotion of the book suggests that the former president’s critics on the left might have been correct all along.

“Regime Change” continues in the same vein. Deneen remains horribly aggrieved by the machinations of “the elites,” particularly in academia, a somewhat ironic stance since he is a faculty member at a prestige university. But after endlessly running down those elites, he proposes to save America by the formation of a “self-conscious aristoi” (the author’s own self-conscious classical reference, an occupational affectation among conservative intellectual wannabes).

And what is this new, self-conscious elite supposed to do? He sees them as an upmarket substitute for the Trump phenomenon, “untutored and ill-led” as it was. One suspects that beneath Deneen’s commonplace academic snobbery about Trump’s redneck followers, his real beef with the lumpen-populists is that Trump succeeded neither in getting himself re-elected nor in staging a successful coup.

Ever since the Joe McCarthy era, conservative intellectuals have played a game of rhetorical obfuscation, never quite coming out and saying that their real problem with America wasn’t with elites or liberals or creeping socialism or a godless civic culture, but rather with the very notion of popular democracy under the rule of law. Deneen at least renders us the service of telling us what he desires: the “overthrow of a corrupt and corrupting liberal ruling class” and its replacement with a new elite, his elite, that would rule through “raw assertion of political power.”

A few years ago one could dismiss that as the metaphorical outburst of a frustrated academic, but after Jan. 6, we all know very clearly what Deneen wants, barely concealed beneath coded phrasing: a violent overthrow of constitutional government. The logical flaw in his whole argument is that, as a coddled academic, he deludes himself into believing that the resulting power structure would consist of Platonic philosopher-kings (perhaps drawn from the faculty lounge at Notre Dame) rather than criminal thugs like Yevgeny Prigozhin.

It is not too much to say that conservative apologetics is a vast rhetorical structure that purports to say one thing when it means another. Economic freedom means the right to exploit one’s natural inferiors; religious freedom equates to imposing religion on sinful unbelievers; defense of tradition means censoring and rewriting history, the better to make the present seem like the culmination of conservative ideas.

Ideas those may be, but the product of genuine intellectuals — those who employ critical reasoning and approach facts honestly — they are not. Ever since the Enlightenment, there has been a perpetual battle, a war of words, between those who would make the world a little freer, a little healthier, a little fairer and a little saner, and those who are viscerally repelled by such markers of secular progress. We see the practical consequences of this conflict everywhere, from the ruined cities of Ukraine to our own barbarously retrograde state legislatures. It is necessary for each of us to know which side we are on in the intellectual struggle of this chaotic century.

Read more

from Mike Lofgren on history, politics and power