What happens when you read an article about climate migration?

After months without rain, your crops have withered away and died, and you’re thirsty. Or maybe you have the opposite problem, and relentless rains flooded your home — not for the first time.

There are lots of reasons people move, and climate change increasingly numbers among them. News headlines warn of a coming “climate refugee crisis,” with rising sea levels spurring mass migration on a “biblical scale.” Provoking anxiety is sort of the default mode for talking about climate change, but is this the best way to discuss people trying to move out of harm’s way?

A new study — among the first to test how Americans react to learning about climate migration — suggests that these kinds of articles might trigger backlash. Both Republicans and Democrats reported colder, more negative feelings toward migrants after reading a mock news article about climate migration, according to research published this spring in the journal Climatic Change.

“There’s a real potential of stories invoking a nativist response, making people view migrants more negatively and possibly as less human,” said Ash Gillis, an author of the study and a former psychology researcher at Vanderbilt University. Depending on how they’re told, stories about climate migration might not only provoke xenophobia, but also fail to rally support for climate action, research suggests.

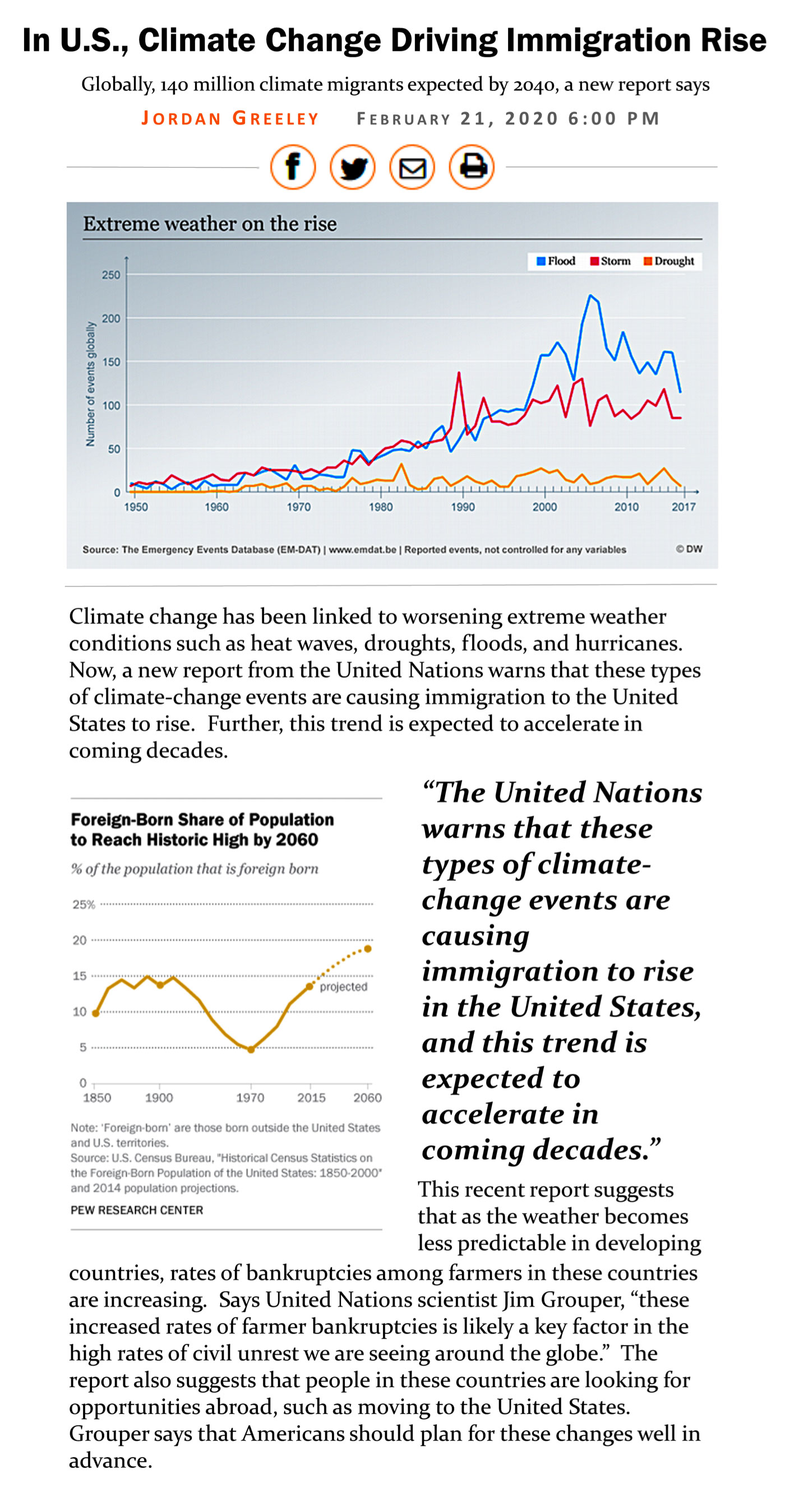

Gillis had been looking for ways to try to reduce polarization around climate change and wondered if pairing the subject with migration might make people more concerned about the changing planet. Instead, Gillis, along with researchers in Indiana and Michigan, found that reading a Mother Jones–style article with the headline “In U.S., Climate Change Driving Immigration Rise” led to more of a backlash toward migrants than reading an article about the country’s foreign-born population rising without an explanation of what was driving it. “There’s something going on with this added climate change component,” Gillis said.

With roughly 20 million people moving in response to floods, droughts, and wildfires every year since 2008, climate migration is already a reality. Most of the time, that movement happens within national borders, with only about a quarter of migrants relocating to new countries. Whether governments respond to those hopeful newcomers by arming their borders or creating pathways for refugees depends to a large degree on compassion. Estimates of how many people will decide to move in the coming decades because of environmental threats range widely, but the stakes could be as high as 1.2 billion lives.

“Figuring out what is the right way to get these messages across is hugely important,” said Sonia Shah, the author of The Next Great Migration. Shah has said that the so-called “migration crisis” is better described as a “welcoming crisis,” suggesting that the real problem lies with how countries respond to the inevitability of migration.

Moving is a destabilizing experience, even under good circumstances, and climate migration is often borne of a traumatic event, like when your home burns down in a fire. But migration isn’t inherently bad: For those on the move, it can be an economic opportunity, or a way of finding safety on a hotter, more unpredictable planet.

“The takeaway shouldn’t be, ‘Let’s avoid [talking about] migration altogether,'” said Stephanie Teatro, director of climate and migration at the National Partnership for New Americans, in response to Gillis’ study.

Protesters take part in a demonstration by the climate activist group Extinction Rebellion, calling for justice for migrants, outside of Britain’s Home Office in central London, April 23, 2023. Susannah Ireland / AFP via Getty Images

Teatro attributes the subjects’ defensive responses to the way politicians and the media have primed them to react. “The study didn’t happen in a vacuum,” she said. Republican politicians peddle myths that migrants steal American jobs or are more prone to commit crimes. But Democrats could be undermining support for immigrants, too, by positioning migration as one of the many distressing outcomes of climate change.

Consider how John Kerry, President Joe Biden’s climate envoy, has approached the subject. “We’re already seeing climate refugees around the world,” he said at an energy conference in Houston last year. “If you think migration has been a problem in Europe, in the Syrian War, or even from what we see now [in Ukraine], wait until you see 100 million people for whom the entire food production capacity has collapsed.” Kerry also once warned that drought in northern Africa and the Mediterranean will lead to “hordes of people … knocking on the door.”

It’s much more difficult to identify with masses of people than a single person, said Kate Manzo, who studies imagery and international development at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom. As an example, she pointed to an anti-migrant poster from that country’s Brexit era showing a snaking line of thousands of refugees that critics said incited “racial hatred.” Describing a group of asylum seekers as a “flood” or “invasion” causes a similar distancing effect, Manzo said.

Even well-intentioned climate advocates like Kerry — in the hopes of bolstering support for reducing carbon emissions — can wind up inadvertently tapping into people’s fears about an increase in migration, Teatro said. “That’s been the default frame: ‘If you want to stop migration, you better get serious about climate change.'”

Research suggests that that type of message may not be effective for motivating policy support for tackling carbon emissions. Learning about climate migration did not increase people’s support for policies such as mandating utilities to get 50 percent of electricity from renewables by 2030 or for making fossil fuel companies pay fees for the pollution they emit, according to Gillis’ study. That finding gels with previous studies showing that framing global warming as a national security issue failed to increase support for climate action, and sometimes even backfired.

Scientists and environmentalists are beginning to recognize that there’s another way of talking about people on the move. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the United Nations’ leading body of climate experts, has acknowledged that migration can be a viable way for people to adapt to a hotter, more chaotic world — provided that the relocation happens in a “voluntary, safe and orderly” manner. A guide from the climate activist group 350.org and other environmental groups calls for reframing the issue (Do: Say migration is “part of the solution.” Don’t: Say “mass migration”). Common Defense, a grassroots organization of progressive veterans, advises against calling climate migration a “crisis” or a threat to national security.

“Migration is a resilient, adaptive response to crisis. It’s not the crisis,” Shah said. “And if we cast it as a crisis, I mean, we’re shooting ourselves in the foot.”

Shah theorized that the wording of the mock news article in Gillis’ study could have prompted a nativist reaction among the study’s participants. It explained that climate change was linked to worsening heat waves, drought, floods, and hurricanes, fueling immigration to the United States. In developing countries, the article said, farmers were going bankrupt, rates of civil unrest were increasing, and people were considering moving abroad — and “Americans should plan for these changes well in advance.” Readers might have taken those ideas and made the trip from “something really scary is happening” to the fearful notion that “brown people are going to come take your stuff,” Shah said.

The mock news article about climate migration from the recent study. Gillis et al.

Shah thinks the framing that climate migration is mostly about poor people moving to rich countries is a “biased way of looking at it.” After all, Americans are moving, too, to escape hurricanes along the East Coast and wildfires in California. Gillis said that the wording of the mock news story was inspired by research that colleagues were conducting on migration and farmers in Southeast Asia.

There are other theories that could explain the backfiring effect. For example, climate change might be viewed as a less legitimate reason for immigrating to a new country than war or famine, Gillis speculated, potentially casting climate migrants in a poorer light. Polling from Pew Research Center shows that nearly three-quarters of Americans generally support the United States accepting refugees from countries where people are trying to escape violence and war, but migration prompted by climate disasters hasn’t yet figured into the polling center’s questions.

“Migration, of course, is a very risky thing to do,” Shah said. “The fact that we’ve done it all along despite the great cost to us in the short term” — from leaving behind our families and friends to getting lost in a new landscape — “what that tells me is that this is something that over evolutionary time, the benefits have greatly outweighed the cost.”

This article originally appeared in Grist at https://grist.org/language/climate-migration-study-articles-xenophobia/.

Grist is a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. Learn more at Grist.org

Read more

about immigration and climate change

By Kate Yoder