How did the zombie become so white?

For all that they are meant to – and do – induce a skin-prickling alarm, the fungal zombies that populate HBO’s “The Last of Us” rely on a stunning optical extravagance that announces them as devices of fantasy. In a bout of poeticism suited to its subject matter, “The Last of Us” has revivified the zombie for fans of serialized horror, attaching it to new origins rooted in biochemistry, a new temporal setting that reimagines the past 20 years as dystopic, and something not-so-new – the preoccupation of much of American zombie media with the dissolution of primarily white suburbs and cities. “The Last of Us” is the latest zombie-horror TV show that allows us to look out on to the marked, magnetic topography of imaginative fiction, but it further distances pop-culture audiences from the distinctly Black source material to which it owes its inspiration – the Haitian zonbi. For many of the Haitians who believe in the existence of zonbi, these figures are as immediate, as personal, as death’s other aspects.

The distress of a loved one’s body gone missing sits at the very center of Haitian folklore.

For many of Haiti’s residents, mentions of the village Titanyen guide to mind the mass graves that, even now, collectively frustrate burial rites meant to aid and/or honor souls as they cut across into the next world. On Jan. 12, 2010, the Haitian capital city of Port-au-Prince was hit by a 7.0 magnitude quake that, all told, killed nearly 300,000 people. It struck in the afternoon while the sun was still propped up quite high in the sky. There were children playing in Port’Prince alleys. In Guantánamo, in Kingston, in Caracas, in Santo Domingo, seismographs registered the quake in mathematical figures while residents of each city felt the ground convulsing for themselves. For days after the quake, the earth near Titanyen was sifted and split for burial pits. Public health officials saw the mass burials as expedient, and necessary, modes of moving the bodies of the dead from Port-au-Prince before decay set in. Many of the deceased were moved before they could be identified by, or have their bodies retrieved by, their families.

For many of the Haitians who had lost loved ones to the quake, the pits were a profane compounding of their grief. In an NPR article published nearly a month after the quake, Haitian mortician Marc Arthur Alcero spoke about how few funerals he had conducted post-earthquake, and how the sparsity was quite disturbing considering the conviction with which the culture honors its dead: “[I’ve conducted] very few of them, about eight or nine. That is very, very hard situation for a Haitian to know his wife, his children is dead, and he cannot find the body.” The distress of a loved one’s body gone missing sits at the very center of Haitian folklore, and this lore, in turn, is an extension of a deeply personal cultural consciousness. Such distress is made particularly manifest in anxieties around one folklore staple – the zonbi, known most familiarly to Western audiences as the zombie.

Men move through collapsed market place along the Grand Rue on February 20, 2010 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, more than a month after the 7.0 earthquake (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)In Haitian zonbi lore, the disappearance of a body from its tomb signals that the deceased person has been taken for reanimation and will be, once returned to a version of living, compelled to do labor for their re-animator in perpetuity. These are anxieties I’ve personally heard expressed in a dozen and one different tones by family members and acquaintances – with humor, because it’s a Haitian necessity to steep about half of whatever serious thing you’re saying in a joke (up to its waist, thereabouts), and with disgust, and with an alloy of anger-and-fear, which springs up into sight then settles down out of sight right at the middle of sentences, gopherlike. “So-and-so’s a fiend, zombifying everything that’s got its eyes closed. Don’t fall asleep around her!”

Men move through collapsed market place along the Grand Rue on February 20, 2010 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, more than a month after the 7.0 earthquake (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)In Haitian zonbi lore, the disappearance of a body from its tomb signals that the deceased person has been taken for reanimation and will be, once returned to a version of living, compelled to do labor for their re-animator in perpetuity. These are anxieties I’ve personally heard expressed in a dozen and one different tones by family members and acquaintances – with humor, because it’s a Haitian necessity to steep about half of whatever serious thing you’re saying in a joke (up to its waist, thereabouts), and with disgust, and with an alloy of anger-and-fear, which springs up into sight then settles down out of sight right at the middle of sentences, gopherlike. “So-and-so’s a fiend, zombifying everything that’s got its eyes closed. Don’t fall asleep around her!”

Their zonbi carries very few of the same physical markers of grotesquerie that much of zombie media has adopted: they are not the itch-inducing, mushroom-headed Clickers of the “The Last of Us” franchise, share no resemblance with the eyeless, needle-toothed “Call of Duty” Crawlers that bound around on all four limbs, and because the body is zombified while it is still fresh, the Haitian zonbi is often clear of the sort of unnerving bodily necrosis popularized by George A. Romero‘s “Night of the Living Dead” film franchise. In fact, it is believed that a Haitian zonbi maintains much of the appearance that it possessed while alive, and they are constantly so close to being returned to a fully live state that the bokor – the sorcerer-for-hire who practices the Vodou faith for both good and evil, depending on client request – must keep them away from the elements that would restore their humanity: salted food, drink, the sight of their home as they’re being marched from their grave or tomb.

The spiritual horror of the Haitian zonbi is that that control, when stripped, is reassigned to whoever has brought the zonbi back from its grave.

For those Haitians who fear it, the Haitian zonbi carries its grotesquerie two ways: 1) the abnormality of having been brought back from the dead, the very fact of having been returned, and 2) the violation of individual will as brought about by a person’s compulsion into posthumous labor. This second form of grotesquerie, this violation of will, has historical heft that partially explains the cultural (meaning Haitian) terror of the zonbi. While the zonbi did, in the era of Haitian slavery, also place as a figure of revolutionary Black immortality that resisted the Black mortality and violent dispensability on which slavery insisted, the apprehension with which those around me approach/discuss/joke about/revile the zonbi is much more in line with this common cultural point reiterated by academic Jeffrey Jerome Cohen: “The folkloric zombie is a reduction of person to body: an utterly dehumanized laborer, compelled relentlessly to toil, brutally subjugated even in death.” This would have been, for the enslaved who shared and reshared this lore, a horror with a metaphysical grip: the notion that they were subject to a second iteration of the slavery that their death should have freed them from.

If the spiritual horror of the zombies in pop-culture juggernauts like AMC’s “The Walking Dead” and critically acclaimed zom-edies like 2004’s “Shaun of the Dead” is that the infected/afflicted have been stripped of their control over themselves, then the spiritual horror of the Haitian zonbi is that that control, when stripped, is reassigned to whoever has brought the zonbi back from its grave, or whoever has paid to have that zonbi “returned.” There is something bitterly disturbing, too, about being turned into a labor-puppet when the pursuit of self-sovereignty in the face of enslavement has always been at the core of your country’s national ethos. Such considerations provide essential context for the way that the zonbi weighs on the psyche of every Haitian person who believes in its existence. Their concern is real, their anxiety potent, because the aforementioned reanimation is a material possibility with the same authority of other dangers –men with machetes, cancer, drowning at sea.

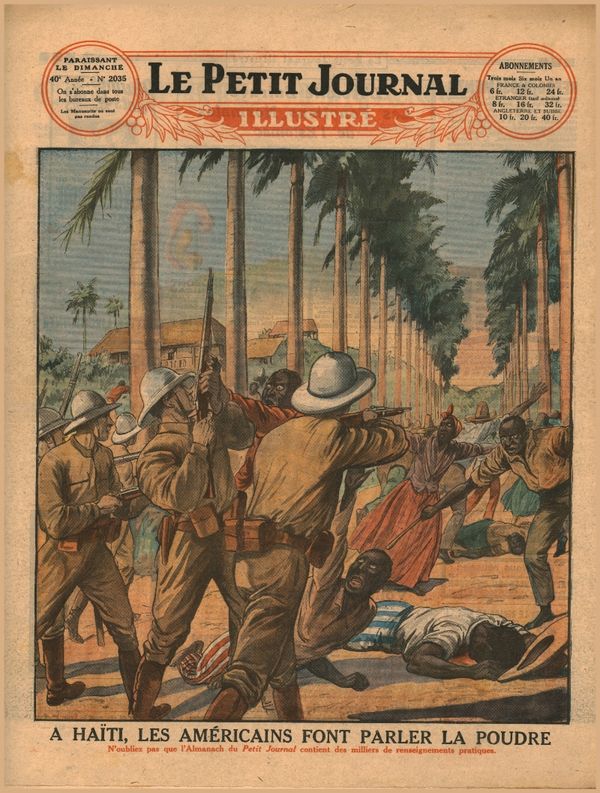

Back cover of “Le Petit Journal Illustré” published Dec. 22, 1929 depicting the Dec. 6 massacre of civilians during the U.S. occupation. The translated cover reads, “In Haiti, the Americans let gunpowder do the talking.” (The Print Collector via Getty Images)The Haitian zonbi, as a concept, entered the 20th-century U.S. imagination at an immediate cultural and emotional remove that obscured the ethnically hyperspecific zombie anxieties I’ve just discussed. That is to say, the zombie arrived in the States mostly absent of the cultural resonance and spiritual gravitas it had, and has, for Haitians in Haiti. It was brought to the attention of many a white American by William Seabrook, who stewarded its entry into the American psychological terrain with his writing of the 1929 book “The Magic Island” during the U.S. occupation of Haiti.

Back cover of “Le Petit Journal Illustré” published Dec. 22, 1929 depicting the Dec. 6 massacre of civilians during the U.S. occupation. The translated cover reads, “In Haiti, the Americans let gunpowder do the talking.” (The Print Collector via Getty Images)The Haitian zonbi, as a concept, entered the 20th-century U.S. imagination at an immediate cultural and emotional remove that obscured the ethnically hyperspecific zombie anxieties I’ve just discussed. That is to say, the zombie arrived in the States mostly absent of the cultural resonance and spiritual gravitas it had, and has, for Haitians in Haiti. It was brought to the attention of many a white American by William Seabrook, who stewarded its entry into the American psychological terrain with his writing of the 1929 book “The Magic Island” during the U.S. occupation of Haiti.

At the time of “The Magic Island’s“ publication, if the journalism around the U.S. invasion of Haiti (for that is what it was) had been any more yellow, it could’ve been added to the national gold reserve to fund further imperialistic excursions. As the country’s leading newspaper, The New York Times vanguarded these racist, sensationalist public impressions of Haiti: a 1926 article asserted that “the U.S. [was] committed to educating the Haitians in self-government,” and in that same piece, The Times endorsed a quote by then Secretary of State Robert Lansing in which he defended the U.S. invasion by pointing to Haiti’s “appalling conditions of anarchy, savagery, and oppression”; The Times spotlighted the dubious congressional testimony of a Marine who claimed that Haitian cacos (anti-occupation resistance fighters) had mutilated and cannibalized American soldiers “according to voodoo custom,” further stoking a national obsession with Haitian cannibalism that had been around since the 19th century, a mania just recently fortified by the publication of a Washington Post article that accused a Haitian woman of “having murdered and eaten live children.”

By the time that Seabrook published his “firsthand account of voodoo in Haiti,” the othering of Haiti, and its Afrocentric vodou religion in particular, had been long underway. Consequently, the social milieu in which many white Americans existed at this time all but guaranteed that the Haitian zombie would become an additional agent for this othering, further estranging Haiti, its people, its lore and the culture from which that lore sprung, from bigoted American conceptions of “civilization” and valuable tradition. The zombie, then, entered a cultural atmosphere already primed to look down on the particular, culturally specific existential fear it generated for Haitians.

To its credit, Seabrook’s book – billed as part-anthropological study, part-Caribbean travelog – keeps zombie lore attached to its Afro-Haitian context. For all that it exoticizes Haiti as a place full of “dark, mysterious” jungle mountains over whose slopes “the steady boom of Voodoo drums” could be heard (even now, these lines make me laugh), even Seabrook positions the zombie as a particularly Black and Haitian phenomenon: “It seems to me that these [Haitian] werewolves and vampires are first cousins to those we have at home, but I have never, except in Haiti, heard of anything like zombies.”

“White Zombie” movie still featuring Bela Lugosi and “Murder” Legendre and Madge Bellamy as Madeline Short (centered) (Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images)

“White Zombie” movie still featuring Bela Lugosi and “Murder” Legendre and Madge Bellamy as Madeline Short (centered) (Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images)

Once it became clear that the zombie could be detached from Haitian origin – excised, unclipped – it then became a sort of mythic free agent.

It seems to me that the true detachment of Haitian origin from zombie lore – within the realm of American pop-culture – began with the release of the film “White Zombie” in 1932, a movie whose screenplay was largely based on Seabrook’s “Magic Island.” In “White Zombie,” a white American woman named Madeleine Short (Madge Bellamy) arrives in Port-au-Prince with her fiance Neil Parker (John Harron); they are to be married on the wealthy Charles Beaumont’s (Robert Frazer) plantation estate, but Beaumont, developing an obsessive sexual and romantic fixation on Madeleine, enlists the help of “Murder” Legendre (Bela Lugosi), a white plantation owner who moonlights as an evil “voodoo” sorcerer, to turn Madeleine into a zombie who will be forever subject to Beaumont’s whim.

On the one hand, Madeleine’s fate in “White Zombie” is a fascinating transposition of the era’s particular and violently racist infatuation with “protecting” the innocence of white women and girls from the “Black male predator,” only this time, nonhuman aspects of “Blackness” – the “black magic voodoo” that white, French-descended Legendre practices, as well as the broader context of Haiti as a Black nation wherein zombification is possible at all – are blamed for the assault.

On the other hand, “White Zombie” drastically de-emphasizes the zombie as a particularly Black phenomenon and repurposes it to explore and indulge and ultimately condemn violent intra-racial gender dynamics. “White Zombie” is ultimately about how white men harm white women, how white people harm white people. In this way, “White Zombie” turns the zombie into a locale of white victimhood.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

With this spinning of zombie lore, zombification became something that could happen to white people; if not in actuality – as the zombie remained and remains a figure of fantasy for many Americans – then metaphorically or imaginatively. This was absolutely crucial for the growth of zombie media away from the Haitian zonbi. Once it became clear that the zombie could be detached from Haitian origin – excised, unclipped – it then became a sort of mythic free agent onto which filmmakers, storytellers and videogame developers, among other creatives, could chart the social anxieties that preoccupied their own communities and intended audiences. The zombie is ambrosia for the mind of the horror-media buff: it possesses the visual and visceral spectacle of necrosis, the ever-present symbology of death, the excitement of the interminably strange.

Most frequently, the zombie of modern-day American media is a vector for societal collapse: this interconnection was popularized by Romero’s 1968 classic “Night of the Living Dead” and, as proven by the gutted material and communal infrastructure of “The Last of Us,” is still strongly present in popular zombie media over five decades later.

“The Last of Us” Clicker at the Bostonian Museum (Liane Hentscher/HBO)In its second episode, “Infected,” “The Last of Us” renders clearly an important detail about this American fixation with zombie-induced societal collapse. Ellie, Joel, and Tess (Bella Ramsey, Pedro Pascal, Anna Torv) pick their way through the former Bostonian Museum, its interior now choked from top to bottom with overgrown vegetation and zombie-making cordyceps vines and the dead bodies of the once-infected. Light pauses on portraits of George Washington, on 18th century colonial military garb, on a peeling illustration of the Boston Tea Party. These images call to mind the colonies’ assertion of white sovereignty, a right-to-rule-the-self exclusive to the wealthy white men of the day; the fact that they are inlaid within the rot and dissolution of the museum interior constitutes an aesthetic mourning for, a loss of, a gilded American society over which white people and institutions presided.

“The Last of Us” Clicker at the Bostonian Museum (Liane Hentscher/HBO)In its second episode, “Infected,” “The Last of Us” renders clearly an important detail about this American fixation with zombie-induced societal collapse. Ellie, Joel, and Tess (Bella Ramsey, Pedro Pascal, Anna Torv) pick their way through the former Bostonian Museum, its interior now choked from top to bottom with overgrown vegetation and zombie-making cordyceps vines and the dead bodies of the once-infected. Light pauses on portraits of George Washington, on 18th century colonial military garb, on a peeling illustration of the Boston Tea Party. These images call to mind the colonies’ assertion of white sovereignty, a right-to-rule-the-self exclusive to the wealthy white men of the day; the fact that they are inlaid within the rot and dissolution of the museum interior constitutes an aesthetic mourning for, a loss of, a gilded American society over which white people and institutions presided.

The zonbi, once it had been spirited across the Caribbean sea within the pages of Seabrook’s travelog draft, became the zombie, the flesh-eater, the dread of slow suburbia. The continued distancing of zombie lore from its Afro-Haitian nativity carries with it a complicated risk: the ubiquity of zombie lore in the States could imbue even its more casual fans with the feeling of expertise, of understanding, which might then be (inaccurately) applied to a culture that has been dogged and demonized and purposefully misunderstood since the revolting enslaved burned down their first sugar plantation in the late 1700s.

“Dézafi” by Frankétienne. Translated by Asselin Charles (UVA Press)Since much of the American audiences for zombie media are familiar with the zombie within the context of art, a more nuanced understanding of the Haitian zonbi may hinge on a sincere engagement with Haitian art that centers the zonbi. Haitian art reifies the zonbi as an active cultural agent, and no medium of Haitian art does this so well as theater.

“Dézafi” by Frankétienne. Translated by Asselin Charles (UVA Press)Since much of the American audiences for zombie media are familiar with the zombie within the context of art, a more nuanced understanding of the Haitian zonbi may hinge on a sincere engagement with Haitian art that centers the zonbi. Haitian art reifies the zonbi as an active cultural agent, and no medium of Haitian art does this so well as theater.

In 2009, the LGBTI theater troupe Lakou, based out of the southern Haitian city Jacmel, staged a production called “Zonbi, Zonbi,” a queer retelling of the Haitian novel “Dezafi” where a zonbi is eventually restored to its humanity by consuming salted food. More than anything, this production situates the zonbi in an anti-colonial space also inhospitable to the homophobia with which colonialism has often been paired. According to performance studies scholar Diana Taylor (2003), “Zonbi, Zonbi” activates a repertoire, “an embodied performance of cultural memory.” Haitian works like “Zonbi, Zonbi” should be watched closely by all interested in zombie lore, because they contend with the zonbi as it first appeared for the island’s earliest Black inhabitants – as a heart thing, as a soul thing, as a scary thing, as a triumphant thing, as a specific thing, as a close, close thing.

Read more

about Haiti